Michelle Marder Kamhi Does Not Consider Photography to Be Art Because

The double portrait of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza past Piero della Francesca in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, is an intriguing masterpiece by 1 of the greatest painters of the Italian Renaissance.

Portraits of Battista Sforza and Federico da Montefeltro, ca. 1473–1475, by Piero della Francesca. Oil on forest. 19 in. 10 13 in. per panel. Uffizi Gallery. (Public Domain)

Most familiar to fine art lovers are its superb profile portraits of ii notable early Renaissance personages. Simply it besides comprises, on the back of the portrait panels, uniquely captivating allegorical scenes, representing each of them in a triumphal procession, above a simulated parapet begetting a Latin inscription.

Triumph of Federico da Montefeltro, by Piero della Francesca. ca.1473–1475. Oil on wood. 19 in. 10 13 in. Uffizi Gallery. (PD-US)

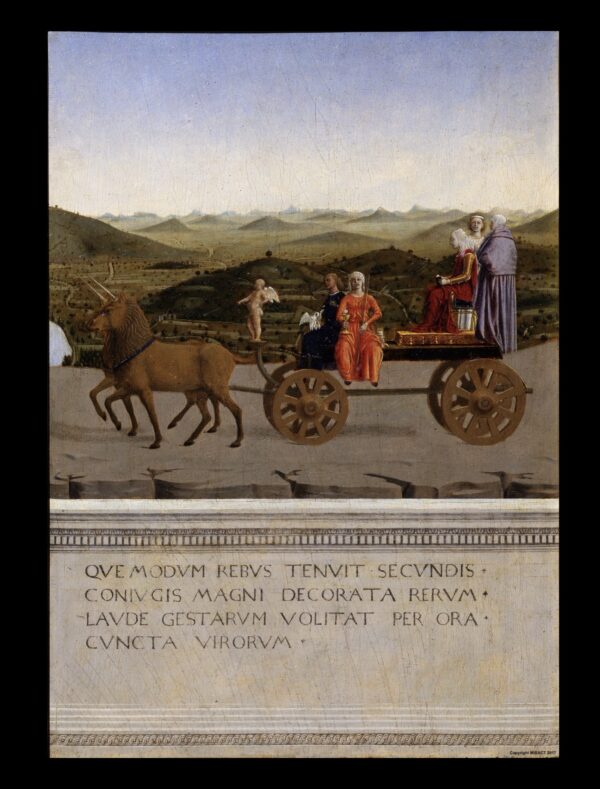

Triumph of Battista Sforza, by Piero della Francesca. ca. 1473–1475. Oil on wood. 19 in. x 13 in. Uffizi Gallery. (PD-US)

Though now displayed in a rigid modern frame, the work was originally designed as a portable folding diptych (two-panel painting), hinged to fold with the emblematic scenes on the exterior. Thus information technology was no doubt intended for intimate personal reflection rather than for public display.

Despite the diptych's artistic quality and distinctive content, no documents take every bit yet shed low-cal on its genesis. Since Federico was a highly erudite patron of the arts, and Piero is known to accept spent time in Urbino during the period leading up to the probable date of the diptych, it has generally been causeless that Federico commissioned the work himself.

In-depth consideration of the piece of work's imagery and inscriptions in the calorie-free of key biographical information about the subjects casts serious doubt on that long-continuing assumption, however. It also suggests a much more than interesting origin, as I will betoken out below.

First, a footling well-nigh the couple represented in the diptych.

Who Were These People?

Federico da Montefeltro (1422–1482) and Battista Sforza (1446–1472) were the count and countess of Urbino, a loma town in the Marches region of eastern Central Italia. The Uffizi Gallery website erroneously refers to them as the "duke and duchess of Urbino." Since Battista died two years before Federico (often spelled Federigo) was elevated to the dukedom, she never became duchess of Urbino.1

Federico was the greatest of all the Renaissance "condottieri" (commanders for hire)—not for his military prowess alone merely for his creation of a ducal court second to none in cultural development and refinement. Baldassare Castiglione's classic Book of the Courtier dubbed him "the light of Italy."ii

Battista—Federico's second married woman—was a scion of the powerful Sforza dynasty centered in Milan. Classically educated and schooled in the formal duties of court life from an early on historic period, she was a remarkably fit consort for Federico, though 24 years his junior. Non yet 14 when they married, she bore him no fewer than seven children and capably managed their domain during his frequent absences in the pursuit of armed services campaigns.

Piero's Depiction

Both Federico and Battista were widely praised in their solar day for their virtuous qualities and their benignancy equally rulers. Piero's delineation of them amply reflects such dignity of grapheme, showing them in dignified profile high above a landscape backdrop suggestive of their domain.

Medal of Federico da Montefeltro, past Clemente da Urbino. 1468. (Saiko/CC-BY-SA iii.0)

Comparing with other portraits of Federico, both earlier and later, reveals the extent to which Piero idealized and refined the battered warrior'due south features to suggest dignity and probity. A telling contrast is the homely eyebrow shown in a medal by Clemente da Urbino dated 1468. Though probably a few years earlier than the Piero portrait, it lacks the vigor of the after delineation.

Less is known almost Battista'southward actual advent. Merely a striking aspect of Piero's depiction of her is her extreme pallor compared to Federico'due south sanguine complexion. While it may only exist due to conceptions of feminine beauty in that era, it has as well been interpreted as indicating that she was no longer living when the portrait was painted.

Significantly, the pairing of such profile portraits with allegorical scenes on their opposite is unique among extant paintings. It was feature of commemorative medals dating back to antiquity, nevertheless, and thus endows the piece of work with a decidedly monumental quality.

The Emblematic Triumphs

The emblematic scenes on the back of the portraits are especially rich, both stylistically and iconographically, and their meaning is enhanced past Latin inscriptions on the simulated architectural parapets below them.

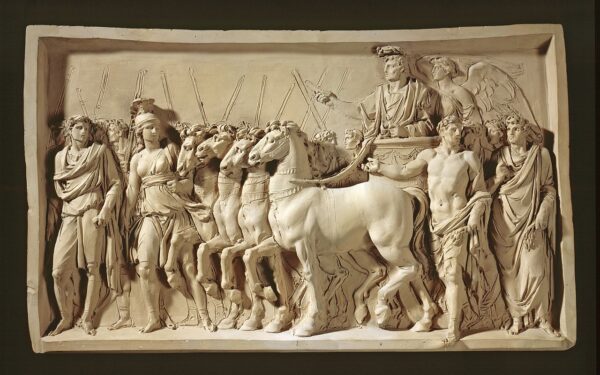

Their iconography draws on a long and complex tradition harking back to Roman triumphs in celebration of major military victories.

Jean-Guillaume Moitte's reconstruction (ca. 1791) of the Triumph of Titus panel from the aboriginal Curvation of Titus, Rome. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (Public Domain)

That tradition had been greatly enriched past a series of allegorical poems penned in the 14th century by the early Italian poet Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch). In contrast to the Roman military machine triumphs, Petrarch'sTriumphs were allegories of philosophic and moral abstractions: Dear, Guiltlessness, Death, Fame, Fourth dimension, and Eternity. Piero's luminous pictorial triumphs contain elements from both the classical and the Petrarchan traditions. Federico'southward triumphal machine is drawn by a team of white horses, as was customary for victorious commanders in antiquity. Like them, he is also crowned by a winged personification of Victory.

In add-on, Federico is accompanied past 4 emblematic figures, seated at the front of his car. They differ from those of Petrarch, even so, instead representing the four primal virtues of the Catholic faith, which also had roots in ancient Greek philosophy. They were Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance—attributes specially relevant to leadership.

In contrast, Battista's triumph represents the three theological virtues, which were by and large regarded as especially relevant to the feminine sphere. They are Religion, Hope, and Clemency. Nigh important here is the effigy of Clemency, who sits at the forefront of the car belongings a pelican.

That attribute has detail significance, as information technology was not generally employed in secular contexts. Because the pelican was believed to pierce its breast to feed its young with its own blood, it had come to symbolize Christ's sacrifice for flesh. Every bit we shall see, it bore poignant relevance to Battista.

Next to Charity is the personification of Faith, holding a chalice and a cantankerous. Continuing backside Battista and facing toward the viewer is the figure of Promise. The other standing figure, garbed in gray with her back turned to us, may represent a nun of the Clarissan order, with which Battista had shut personal ties.

As in Petrarch's Triumph of Chastity, Battista'south triumphal automobile is fatigued by unicorns, emblematic of Chastity, farther suggesting her virtuous character.

The Latin Inscriptions

Important clues to the date and genesis of the diptych are offered by the prominent transcriptions below the triumphal scenes. Federico'south inscription clearly alludes, in the present tense, to his greatness equally a commander. Rendered in English it reads:

The famous one is drawn in glorious triumph

Whom, equal to the supreme age-old captains,

The fame of his excellence fitly celebrates,

As he holds his scepter.

In contrast, Battista's inscription begins by referring to her in the past tense.

She who retained modesty in practiced fortune

Now flies through all the mouths of men

Adorned with the praise of her great husband's deeds.

Moreover, the phrase "flies through all the mouths of men" echoes lines that the Latin poet Ennius had penned as his epitaph:

Let no one honor me with tears or on my ashes weep. Why?

I fly living through the mouths of men.

Made famous by the more than eminent Latin writer Cicero—who quoted them in his philosophic meditations on decease—the epitaph of Ennius was taken to mean that the fame of a virtuous person extends across death.

The clear implication of Battista's inscription, therefore, is that she was no longer living when the diptych was created.

Who Commissioned This Remarkable Work?

In his 2014 biography of Piero della Francesca, James R. Broker argues (based in function on the Latin transcriptions) that the diptych was painted "presently subsequently Battista's expiry," and that information technology was commissioned by Federico "to memorialize his wife and their marriage."3

While I agree most the date, I have long believed that Federico's commissioning the diptych would have been incompatible with the tragic circumstances surrounding Battista'southward death. Let me summarize the primary events here.

When Battista died, in early July 1472, Federico had but returned dwelling post-obit his about celebrated military entrada. On behalf of the Medici rulers of Florence, he had suppressed a rebellion by the metropolis of Volterra, a mineral-rich Florentine tributary. In gratitude, the metropolis of Florence had granted him the rare tribute of a live triumph, to which Piero's pictorial triumph may well allude.

Equally important, in January of that yr Battista had at last given birth to the couple's but son and heir, Guidobaldo—after 11 years of spousal relationship, during which she had borne at least six daughters. The death of his young married woman then soon after that joyous event inspired intense mourning on Federico's part, and an outpouring of sympathy throughout Italy.

To chemical compound the tragedy, it was reported that Battista had prayed for a son and heir worthy of her noble husband, offer her own life in return—a pledge she had now fulfilled. The pelican of Charity in her triumphal scene is a likely allusion to that cede.

Given that sorrowful context, I argued decades ago in a thesis on the diptych that the verses inscribed under the triumphs "strike a jarring notation."

The proud vaunt of Federico's inscription seems inappropriate to his grief. And the meager praise of his beloved countess, whose fame is said to derive not and then much from her own virtue equally from the deeds of her famous husband, is an ungenerous … last tribute; one would think that the paintings were more a monument to Federico than a celebration of his consort. Surely this is not the near plumbing fixtures memorial a bereaved married man could devise for a wife who was eulogized past all Italian republic.four

Consequently, I proposed that the diptych had been commissioned for Federico, not past him—as both a tribute to him and a consolation for his nifty loss.

As I further suggested, it is tempting to think that the donor of such a splendid gift might have been none other than the eminent patron of the arts Lorenzo de' Medici—who would take had item reason to honor Federico, given the crucial victory at Volterra.

This slice is based on my M.A. Thesis (most which, run into "Remembering Howard McP. Davis," For Piero's Sake, Oct 20, 2020). It was originally published, without notes, in Epoch Times, September i, 2021.

Notes

- Battista is properly referred to as "Countess" by Elaine Hoysted, for instance, in "Battista Sforza, Countess of Urbino: A Privileged Status in Motherhood," Socheolas: Limerick Pupil Periodical of Sociology, Vol. 4(1), April 2012, 100–116. ↩

- Denis Mack Smith, "Federigo da Montefeltro," in The Horizon Book of the Renaissance (American Heritage Publishing, 1961), 321-28. ↩

- James R. Broker,Piero della Francesca: Artist & Man (Oxford Academy Printing, 2014), 146–51. ↩

- Michelle Kamhi, The Uffizi Diptych by Piero della Francesca: Its Grade, Iconography, and Purpose . Chiliad.A. thesis, Hunter Higher, C.U.Due north.Y., 1970, 52. ↩

Source: https://www.mmkamhi.com/blog/

0 Response to "Michelle Marder Kamhi Does Not Consider Photography to Be Art Because"

Post a Comment